How does this encounter make you feel?

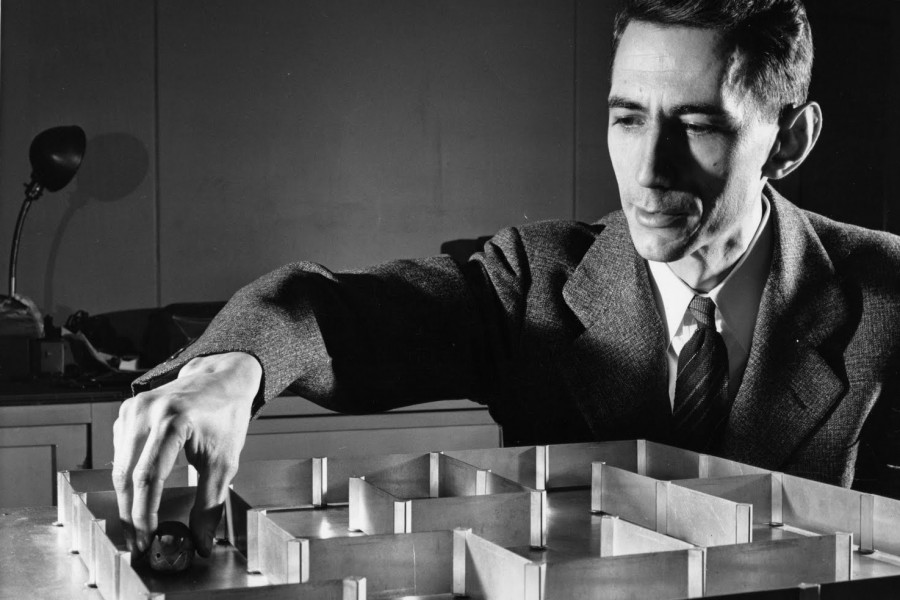

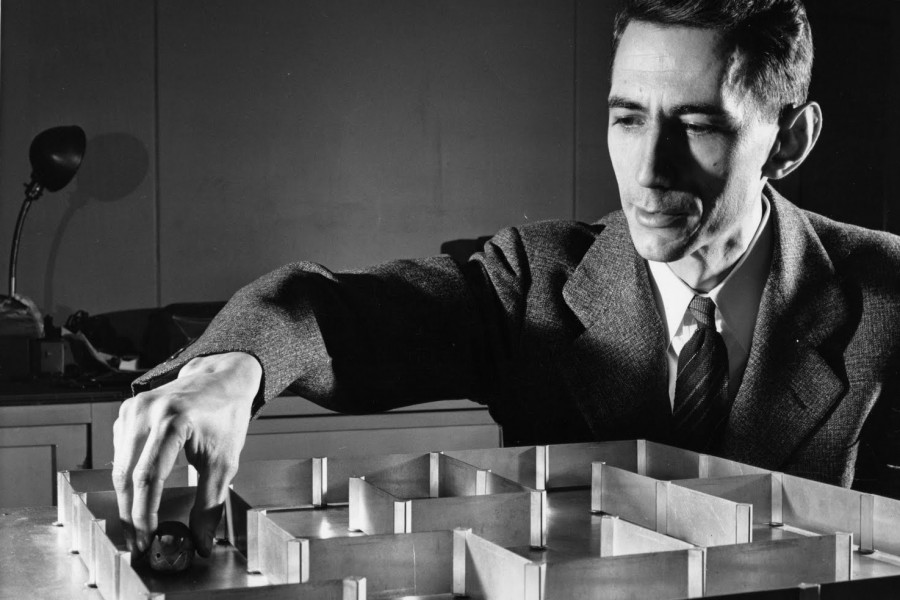

Theseus, a robot rat, runs a maze set up by Claude Shannon,

c. 1952

-

Bright emotions

-

Not at all Extremely

-

-

Quiet emotions

-

Not at all Extremely

-

-

Heavy emotions

-

Not at all Extremely

-

-

Sombre emotions

-

Not at all Extremely

-

Compare yourself to others

Choose different variables below, and see the patterns of response reflected in the circle of emotion above. Your responses are the coloured wedges. Others' responses are averaged in the spider graph of lines and dots.

Date: c. 1952

Creator of the image: Bell Laboratories Date of the image creation: c. 1952 Medium: Photograph Person depicted: Claude Shannon This photograph depicts Claude Shannon in 1952 with Theseus, the epic Greek name he gave his electronic mouse (in 1951 was originally given the name ‘Rat’). Created in the 1950s, this mouse was programmed to move around a labyrinth made of 25 squares, finding its way and adding new information to its memory. This robotic mouse represents one of the first steps towards attempting to develop artificial intelligence. Rebecca Lemov (2011) records that ‘Rat’ first debuted in 1951 at the Macy Foundation conference on cybernetics, engendering both elation and pathos: ‘Rat riveted a crowd of twenty-five of the nation’s foremost social, behavioral, and physical scientists. They had gathered for the eighth of ten meetings unified under the theme of “Circular and Causal Feedback Mechanisms in Biological and Social Systems”. What had them on the edge of their seats was not just Rat’s clever engineering. The maze-solving machine was in fact very simple, made of a “sensing finger” hooked up to two motors, one that operated in the east-west, the other in the north-south direction. By means of these components it could maneuver whatever configuration of the maze — for the structure had moveable walls — Shannon chose to arrange. What gripped the audience was a quality akin to pathos: rather than watching something (say, a highly trained lab rat) simply succeed automatically in solving a maze, the audience was watching it trying, failing, testing, going awry, and finally making its way. The electronic rat and maze were one system, and the system, in an “all too human” way (in the words of one onlooker), worked. Rat learned. This struck the assembled crowd as significant. It offered a model on which all kinds of social and biological systems could be based.’ She continues: ‘The same year as Rat performed its twin futures a new paradigm in the American behavioral sciences emerged called coercive persuasion – and, I argue, these two events shared a common genesis in theories of systems. Coercive persuasion was the US scientific response to the political-intellectual crisis about communist brainwashing capabilities that in the early 1950s gripped high-up levels of government and quickly spread through popular audiences. U.S. Air Force pilots appeared in newsreel footage blaming imperialism and admitting to germ-warfare missions; twenty-one American GI’s held as Korean War POWs defected to communist lands; and there appeared to be a blind spot in American individualism, which was evidently vulnerable to Manchurian-Candidate-style ideological engineering. A fleet of behavioral scientists took on the task of studying this phenomenon … The resulting science of coercive persuasion, sometimes also known as “forceful interrogation”, was based on viewing the prisoner within his situation as a single system, much as Rat in his electronic maze made up a system. No longer was the prisoner seen primarily as an individual exerting heroic effort — or failing mightily — against forces that threatened to break him down into a dehumanized shell of his former self. Instead, a systems approach to coercion viewed the individual-within-the-environment as a set of circulating messages.’ This process gave rise to the science of ‘soft torture’, the progenitor to ideas systematically used in Abu Ghraib. Claude Shannon (1916–2001) was an eccentric mathematician and electrical engineer whose theories and inventions played an important part in the history of computers. ‘Scientific American’ called him the ‘father of information theory’. While Shannon had nothing to do with the development of ‘soft torture’, he did have a military background, joining the war effort as a researcher in the 1940s. He worked on a project developing fire-control mechanisms for anti-aircraft guns, and also as a cryptographer developing encryption techniques to allow secret communication between Franklin D. Roosevelt at the Pentagon and Winston Churchill in his War Rooms. During this time, Shannon laid down the basis of information theory, which he formally spelled out in a famous paper published in 1948. Information theory sits at the intersection of applied mathematics, electrical engineering and computer science, and it is fundamentally concerned with the quantification, storage and communication of information. Shannon expressed activity hostility towards meanings that could not be quantified. He said that there is no difference between ‘a random sequence of digits, or… information for a guided missile or a television signal’.